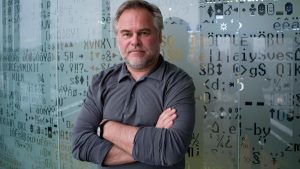

Eugene Kaspersky got into computer safety by accident. Now the Russian billionaire is creating a €5m office in Dublin

If you run a global cyber-security company and your job is to combat cyber-criminals and overcome attacks against nuclear facilities and hospitals, it pays to be paranoid, says the Russian billionaire Eugene Kaspersky.

In a private meeting room at Dublin’s Shelbourne hotel, following the launch of Kaspersky Lab’s only R&D centre in the EU, Kaspersky is open and affable — and far from paranoid. Yet his business and personal life have taught him not to trust technology and people who may misuse it for their own benefit.

His son Ivan was kidnapped in 2011 while using Vkontakte, a Russian social network. Ivan, then 20, had been tracked online and abducted by a gang in Moscow who demanded more than €3m for his release.

Kaspersky stalled the kidnappers with promises to pay up. With the help of a crack team from the FSB, Russia’s federal security service, Ivan was rescued, unharmed, four days later.

“I am right to be professionally paranoid,” says Kaspersky. “If he [Ivan] made something public, he couldn’t wipe it because it’s there forever. I am really surprised that my kid has not learnt from it and may still be on that network.”

An adrenaline junkie, Kaspersky, 50, eschewed his usual denim uniform for the Dublin visit, and wore an Italian suit and a crisp, white shirt to join Enda Kenny at the jobs announcement.

In the week when the EU state aid ruling on Apple engulfed the cabinet, Kaspersky Lab — one of the world’s biggest IT security companies — was keen to keep a distance. The company, registered in the UK, is not in Ireland to dodge tax, says Kaspersky. “My company doesn’t behave like this and we don’t have any plans to behave like this,” he says. “To be a Russian company we have to behave more transparently than others.

“We are a security company, and the security business is a business of trust, just like financial services. If you don’t trust the bank, you are not a customer. It’s the same for security companies. The security business is a business of trust and, if we play a tricky game, it looks bad for us.”

Kaspersky says he was attracted to Ireland by its brain power rather than the low corporate tax base. His Moscow-headquartered company is investing an initial €5m in its R&D operation and creating 50 jobs. The Dublin team, headed by local hire Keith Waters, has just taken half a floor in 7 Grand Canal, a building recently refurbished by its owner, Aviva Investors.

“We don’t have any plans to have taxation here,” says Kaspersky. “We pay our corporate taxes in London. We are a security company and we have to be 100% transparent and far away from any questions of trying to evade taxation.”

Following the Brexit vote, Kaspersky has no plans to “jump ship” and leave the UK, where his European head office and holding company are located. So there are no immediate proposals to have sales, marketing or finance roles in Dublin, but he may create a training centre in the city, dedicated to education in emerging cyber-security fields such as critical infrastructure protection and transportation security.

Dublin, home to many of the world’s leading cyber-security firms, was the only city in the running for the European R&D centre.

“I know two nations where governments speak the business language and trade the nation as a business in a good way. They are Singapore and Ireland,” says Kaspersky.

“Singapore’s development agency works in the same way, but in Singapore they are suffering from a lack of R&D and their engineering labour market isn’t as good as Ireland’s.”

Nevertheless, it took a tag team of the taoiseach and Bono, with backing from the IDA, to convince and cajole Kaspersky to set up in Dublin. The Russian tycoon, who has a net worth of $1.1bn (€980m), was wined and dined by Kenny and the U2 singer after attending the Web Summit two years ago.

“The taoiseach had a presentation and mentioned our company a number of times,” says Kaspersky, who first visited Ireland a decade ago. Later, the Russian was at a dinner table, with Kenny in front of him and Bono to his right. “It was great and it was also a very big surprise to find Ireland has the kinds of experts here that are harder to find than in other nations.”

Kaspersky’s only regret was to miss out on Bono’s infamous pub crawl during the summit. “I would have loved to have been on it,” he says.

Born in the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk, Kaspersky grew up near Moscow, to where he moved aged nine. His father was an engineer and his mother an historical archivist. As a child he developed an interest in maths and technology, and at 12 he was studying advanced maths at an evening school for children. He entered a local maths Olympiad, finishing second.

In 1987, Kaspersky graduated from the Institute of Cryptography, Telecommunica- tions and Computer Science in Moscow, known during the Cold War as the Technical Faculty of the KGB Higher School. He got into cyber-security by chance when his computer became infected in 1989 with the Cascade virus, which made characters on a screen tumble to the bottom like Tetris blocks. He analysed the encrypted virus, got to understand its behaviour, and developed a tool to remove it.

Curiosity and a passion for computer technology drove him to start studying more malicious programs and develop software to deal with them.

At 24, Kaspersky created his first antivirus software, to protect his computer. Eight years later he founded Kaspersky Lab, now the world’s fourth-biggest antivirus maker, with 3,300 staff in 32 countries.

The company’s software has 460m users. Revenue has grown from $2m in 1999 to €711m last year, all achieved organically. In 2012, Kaspersky shocked investors after abandoning plans for an IPO in New York, saying it would slow decision-making and hinder long-term R&D investments.

The fallout from the collapsed deal led to departures of senior figures including his co-founder and ex-wife Natalya. Kaspersky also bought out General Atlantic, one of his long-time private equity partners.

“We have no plans to go public,” he says. “We behave almost like a public company insofar as we publish extensive financial data. We are self-funded and now we invest in cyber-security start-ups.”

Kaspersky’s home market of Russia has been hit by a two-year recession and a rouble devaluation, yet the country accounts for only 12% of group revenues. The main market is western Europe, which accounts for one-third of revenues, followed by America, with about a quarter.

Nobody is immune from cyber attacks, according to Kaspersky, who admitted that his company was hit by one such incident last year. A group gained access to data related to R&D and new technologies, yet there was no disruption to any of the company’s products or clients.

“I don’t want to point the finger, but it was definitely a state-sponsored attack,” says Kaspersky. “First of all I was surprised and angry, but then I thought this is good news. We do such a good job that they want to know what we are working on right now.”

In Russia it can be difficult for high-profile businesses to succeed without close links to Kremlin structures, and Kaspersky is often accused by western media of being too close to the ruling party. President Vladimir Putin, a former KGB lieutenant colonel, once invited Kaspersky to the Kremlin to honour him with an award. Bloomberg ran a long report on Kaspersky about hiring former KGB staffers, only for competitors to jump to his defence, as many cyber- security companies hire staff from secret services.

Kaspersky maintains that his staff work with all law- enforcement agencies and points to several instances when his team has helped Interpol, Europol and other foreign police organisations fight cyber-crime and identify those responsible for it.

“Everyone spies on every- one,” says Kaspersky. “Who is the best and who is the worst? I don’t know, because we don’t see all the victims and all the attacks. Many are invisible and many are very professional, and maybe they will stay invisible for ever.”

Kaspersky is not a fan of Edward Snowden, the former National Security Agency contractor who has been accused of being a Russian spy. Snowden has lived in Moscow for three years, having orchestrated the biggest leak in US intelligence history.

“Snowden violated the contract with his employer, which is bad,” says Kaspersky. “I don’t respect this kind of behaviour. It’s the wrong way of fighting for freedom.”

Kaspersky travels the world to promote his company and products. He drives racing cars as a hobby and Kaspersky Lab sponsors the Ferrari Formula One racing team. The tycoon has also been known to hike up Russian volcanoes, and once reserved a seat on the planned Virgin Galactic trip into space.

The sense of adventure does not stretch to his mobile phone where, one suspects, professional paranoia is at work again. From his jacket pocket he produces a basic phone made eight years ago by the now-defunct Sony Ericsson.

“It just makes calls, sends text messages and has an alarm call,” he says. “I like it. If I need more, I just say to a colleague, ‘Give me your phone.’”

“I tried the iPhone, Samsung and others, but I realised I don’t need all those buttons and all the stress.”

The life of Eugene Kaspersky

Vital statistics

Age: 50

Home: Originally from the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk; lived in Moscow since the 1990s

Family: Married three times; four children

Education: Degree in mathematical engineering and computer technology from Moscow’s Institute of Cryptography, Telecommunications and Computer Science

Favourite book: Most of the books by brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Russian science-fiction authors

Favourite film: Blade Runner, pictured above

Working Day

When I’m in Moscow I usually wake at 9am. I arrive at the office at 11am — I’m not a morning person — and start by reading the news, emails and reports from the departments. Sometimes I try to squeeze in a workout in our office gym. I typically have several meetings a day, internal and external. I talk regularly to my top R&D people about how our most important projects are going, but prefer not to micromanage or get involved in detailed discussions. That’s my management philosophy — hire the right people who you can trust to get on with the job, and don’t interfere in how they go about doing it. I try to leave at 8pm to go home for a meal with my family, but sometimes I stay till late.

Downtime

When travelling on business – I do that about six months of every year – I like to do sightseeing on quick walkabouts when I get free time. I love to get out into the countryside and do hillwalking or something more extreme, like white-water rafting or volcano climbing. I read a lot, mostly science fiction or non-fiction — history, business, biographies — and I love watching films. All very ordinary, really.